This article on ‘SC Upholds 10% Quota for Economically Weaker Sections‘ was written by an intern at Legal Upanishad.

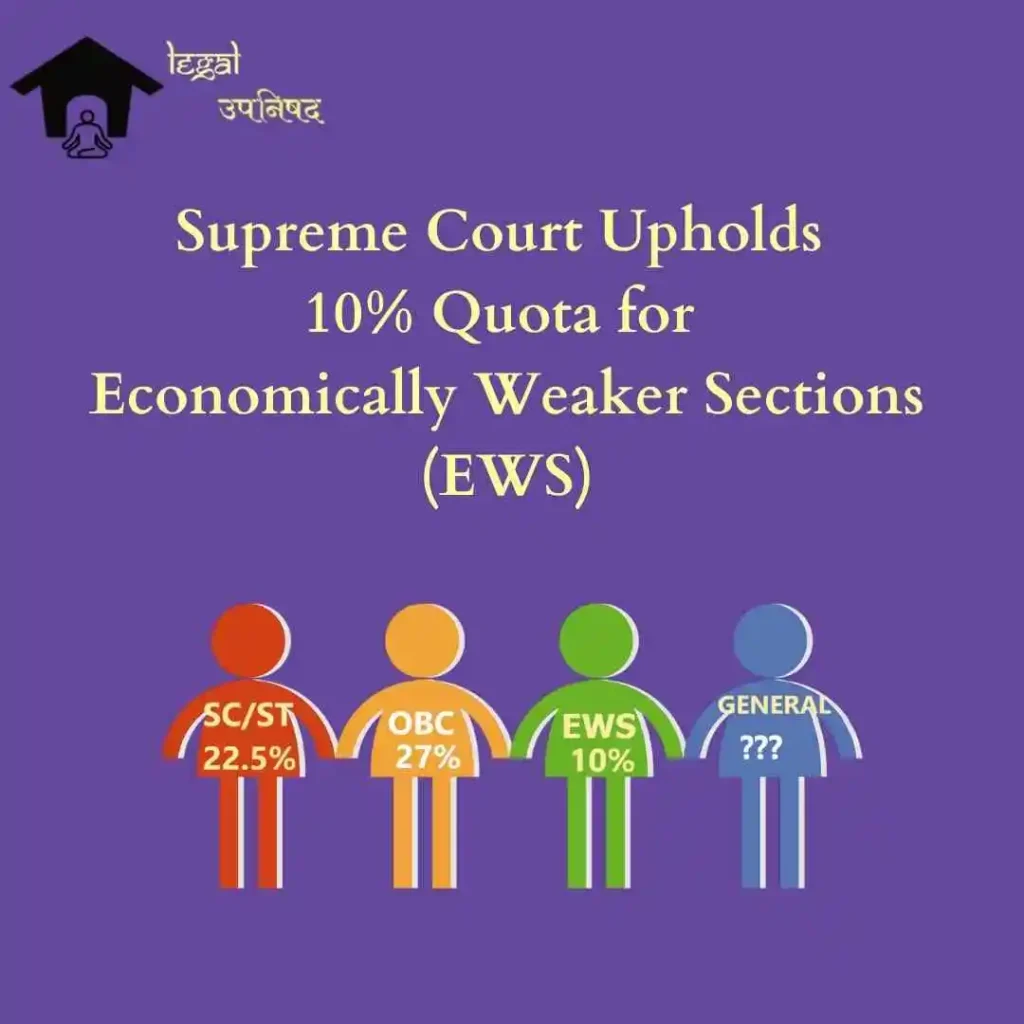

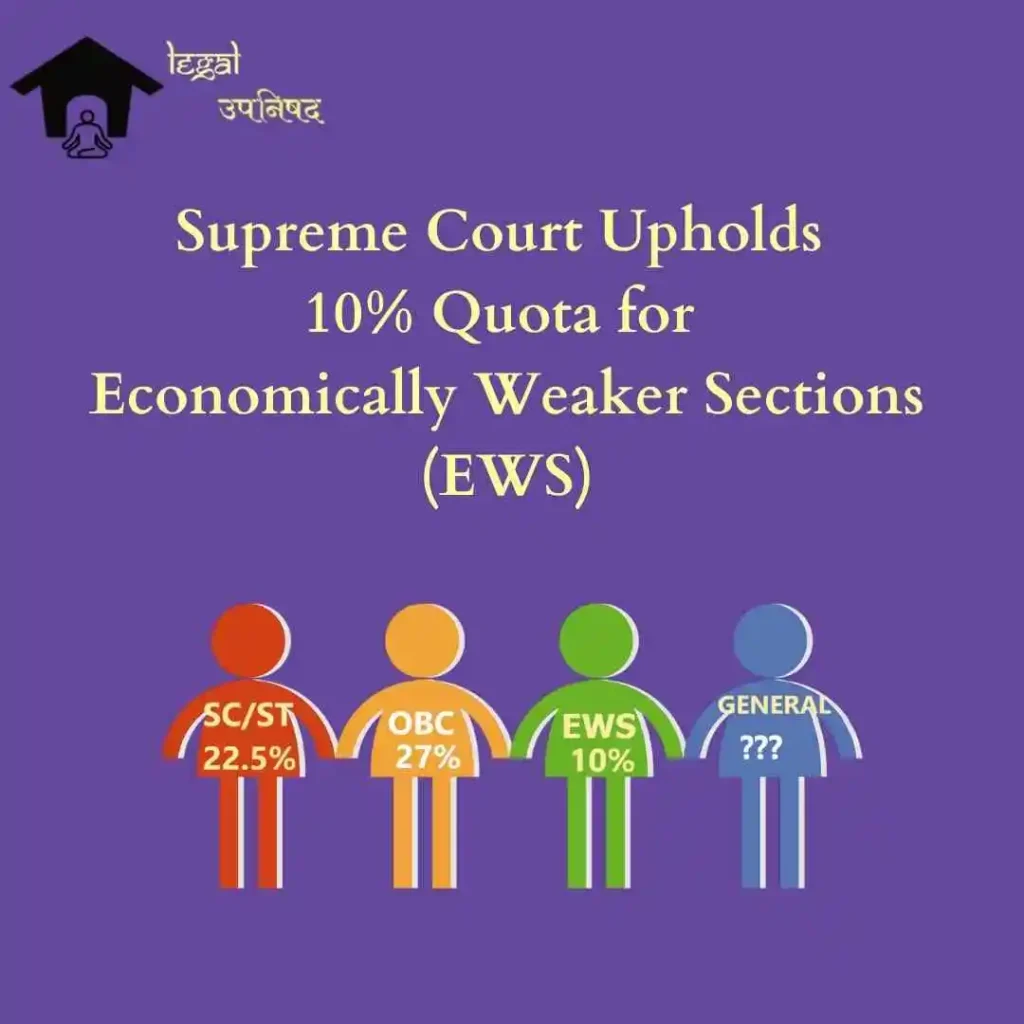

In a significant decision, the Supreme Court confirmed the constitutionality of the 103rd Amendment, which grants members of the economically weaker sections (EWS) a 10% reserve in admissions and government employment. The court ruled that the EWS quota regulation did not contradict the Constitution’s fundamental principles.

Background

The Bharatiya Janata Party-led Union government implemented the 10% reservation for economically weaker sections of the general category, which includes individuals who do not belong to the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, or Other Backward Classes, through a constitutional amendment in January 2019. All government positions as well as privately and publicly supported educational institutions were subject to this new quota. However, minority-run educational institutions were exempt from having to impose EWS reservations.

Economically weaker sections were those whose annual household income was less than Rs. 8 lakh or whose property holdings fell short of the thresholds it set. In a different case, the Supreme Court is debating the validity of this definition.

One of the legal issues covered was whether the 103rd Constitutional Amendment violated the Constitution’s fundamental principles by allowing the State to impose special rules, such as reservations, based on economic criteria or by allowing the State to impose special rules for admission to privately run institutions. The 103rd Constitution Amendment, according to one argument, violates the 50% cap on reservations set in the 1992 Indra Sawhney case, often known as the Mandal Commission case, among other things. According to the ruling of the nine-judge panel in the Indra Sawhney case, “reservation should not exceed 50%, excluding some extreme cases.”

Judgments

The Union’s arguments were accepted by Justices Dinesh Maheshwari, Bela Trivedi, and JB Pardiwala, who in three distinct but concordant judgments upheld the constitutional legitimacy of the EWS reservation. They argued that only economic considerations may be used to grant reservations.

Maheshwari believed that discrimination might result from poverty and that reservations were meant to lessen social disparity. According to him, achieving “substantive equality” means ensuring both social and economic justice.

Maheshwari pointed out that since all reservations have an exclusionary nature, excluding disadvantaged groups from the EWS reservation is not very different from excluding members of the general category of the economically weaker sections from reservations for people belonging to the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes. Because the 50% ceiling is flexible and only applies to the reservations envisioned under Articles 15(4), 15(5), and 16(4) of the Constitution of India, Justice Maheshwari stated that the amendment did not harm the fundamental structure of the Constitution by exceeding the 50% threshold.

According to Justice Pardiwala, reservations shouldn’t last indefinitely. Baba Saheb Ambedkar believed that by instituting reservation for just ten years, societal harmony could be brought about. But it has persisted for longer than seven decades. In order to develop a vested interest, reservations shouldn’t last indefinitely, he stated.

Furthermore, according to Pardiwala, economic reasons might be used both ways to extend reserves if they could be used to deny them to some groups, such as the “creamy layer” of the Other Backward Classes. Given that “just a small percentage of [the] population…is above the poverty line” in India, Pardiwala said that denying the EWS reservation would be equivalent to depriving “those who are qualified and deserving what is or at least should be their due.”

“However, at the end of seventy-five years of our independence, we need to revisit the system of reservation in the larger interest of the society as a whole, as a step forward towards transformative constitutionalism,” Justice Trivedi, the lone female judge on the bench, wrote in her 24-page concurring views with Justice Maheshwari.

She and Justice Pardiwala argued that reservations must have a time limit since they cannot last indefinitely. Justice Pardiwala authored a concurring 117-page verdict sustaining the EWS quota.

The judges said that they had followed Parliament’s judgment as well. According to Trivedi, if the legislature’s actions had a valid justification, the court could not invalidate a constitutional amendment because the legislature is aware of the requirements of its people.

Dissenting Judges View

Justice Bhat and Chief Justice U.U. Lalit disagreed with the other three judges sitting on the bench. The statute said to Chief Justice U.U. Lalit and Justice Bhat are discriminatory and go against the Construction’s fundamental principles.

Justice Ravindra Bhat argued that while the exclusion of equally impoverished groups of society, such as SC, ST, SEBC, and OBCs, amounts to a “constitutionally prohibited form of discrimination” even though the EWS quota’s underlying premise appears to be that of economic deprivation and penury. The backward classes should not be included in the Amendment’s scope, he added, even though it is still valid. He warned that allowing a breach of the 50% allocation for underprivileged groups would result in compartmentalization.

As Justice Bhat put it, reservations made on the basis of economic criteria are legitimate in and of themselves, but excluding other backward people (SC/ST/OBC/SEBC) violates the fundamental principles of society. It is discriminatory to just help the poorest, regardless of caste or class.

In addition, Justice Bhatt emphasized that in India, 48% of Scheduled Tribe and 38% of Scheduled Caste people live in poverty. As a result, it is impossible to say that excluding this group is constitutional.

More specifically, they claimed that to exclude these populations “on the ground that they receive pre-existing benefits, is to heap fresh injustice based on prior incapacity.” This exclusion violated the principle of “non-discrimination and non-exclusion which forms an inextricable part of the basic framework of the Constitution” because it was based not on their deprivation but rather on their “social background or identity.”

Even so, both of these justices conceded that economic considerations alone might be the basis for discrimination in educational institutions. Looking at reserves via deprivation provided a “new dimension”.

Conclusion

Whether the new quota violated the Constitution’s fundamental principles was the main issue before the top court. The petitioners had contended that economic backwardness should not be addressed through reservation and that the Constitution’s framers did not intend for economic backwardness to be a prerequisite for reserve. They argued that only broad categories cannot be used to provide economic reservation. This would be against the equality code, a fundamental tenet of the Constitution that has long been recognised.

According to the petitioners, the EWS reservation’s exclusion of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes from the benefit would violate the principle of equality. The government’s legal team contended that since this 10% quota is in addition to the existing reservation, the Constitution is not being violated. The EWS reservation has been defended by the state on the grounds that it has a duty to protect the weaker segments of society. According to government attorneys, the only reason to reject a constitutional change is a violation of its fundamental principles.

Reference

- Umang Poddar, “Why the Supreme Court upheld the validity of quotas for the Economically Weaker Sections”, Scroll, available at: https://scroll.in/article/1036886/explainer-why-the-supreme-court-upheld-the-validity-of-quotas-for-the-economically-weaker-sections

- Haraprasad Das, “Supreme Court UPHOLDS 10% Quota For Economically Weaker Sections (EWS)”, Pragativadi, 7 November 2022, available at: https://pragativadi.com/supreme-court-upholds-10-quota-for-economically-weaker-sections-ews/

- Anindayq Thakuriya, “EWS Reservation: Supreme Court Upholds Constitutional Amendment, BQ Prime, 7 November 2022, available at: https://www.bqprime.com/law-and-policy/ews-reservation-supreme-court-upholds-constitutional-amendment